Audio Post Production Research Regarding LO2

Before I look into more detail about sound design and post production I want to research and define audio post production, what is involved and what the roles are involved. filmsound.org is a great site used to learn more about film sound. It contains articles and tips to improve your film sound skills.

One of the pages in this site called “Post Audio FAQ’s” does a great job at defining audio post production and what is involved:

|

“POST AUDIO FAQ’s” Frequently Asked Questions About Film & TV Post-Production What is Audio Post-Production?Audio Post-Production is the process of creating the soundtrack for a visual program of some kind. Ever since silent movies began to talk, filmmakers have been looking to control and improve the quality of the sound of their creation. As soon as creators realized there was a way to control and enhance the sound of their pictures, Audio Post was born, and has been a fact of life ever since. In Television, audio was originally “live”, like the visual program it was part of. As TV evolved, and the art form grew to include “videotaped” and “filmed” programming, the need for Audio Post increased. Nowadays, it would be difficult to find any feature film or television show that hasn’t been through audio post. What is involved in Audio Post ?Audio Post usually consists of several processes. Each different project may need some, or all of these processes in order to be complete. The processes are:

What does all that mean in English ?It’s really pretty simple, once you know the breakdown::

|

Where does post-production begin ?

If you haven’t shot your film yet, it begins before you shoot – by selecting the finest production dialogue mixer you can afford. The little bit extra paid to a great production mixer can save you tenfold later in post-production.

What happens during the mix ?

During the mix, the edited production dialogue and ADR, sound effects, Foley and Musical elements that will comprise the soundtrack are assembled in their edited form, and balanced by a number of mixers to become the final soundtrack. In New York, single-mixer sessions are more commonplace than in Hollywood, where two-mixer and three-mixer teams are the norm.

The mixers traditionally divide the chores between themselves: the Lead Mixer usually handles dialogue and ADR, and may also handle music in a two-man team. In that case, the Effects mixer will handle sound effects and Foley. In three-man teams, they usually split Dialogue, Effects and Music; sometimes the music mixer handles Foley, sometimes the effects mixer covers it.

To keep the mix from becoming overwhelming, each mixer is actually creating a small set of individual sub-mixes, called STEMS. These mix stems (dialogue, effects, Foley, music, adds, extras, etc) are easier to manipulate and update during the mix.” (filmsound.org)

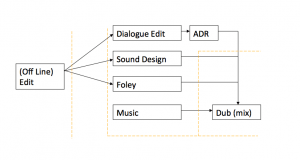

The Process that FilmSound.Org is describing also matches the post-priduction role flow chart, that was shown to us in a lecture from Grant Bridgman in the 1st and 2nd year:

The audio post production process in my project will work in a very similar way with some minor differences. In the section “what is involved in Audio post?” it simply says the different processes of audio post production. With the two films I am performing or undertaking different roles. For ‘All Ribbons End’ I will be undertaking all roles within audio post excluding music composition. With petal Child I will be undertaking a supervisory role as well as dialogue editing and mixing (dubbing). The rest of the post production will be completed by Sid including music composition, sound design and Foley.

My process will start also with production dialogue editing. This will be followed by any ADR, voice overs, dialogue recording that is required. On the two films there needs to become form of dialogue recording in the post production. All ribbons end needs the voice of a call operator and a bingo caller. Petal child requires the sound of someone shouting in an authoritative manor in the first scene. ADR may be required however due to strict time- restrains and actor’s availabilities this may not be possible. Therefore a lot of effort and attention to detail needs to be put in place to avoid the need for ADR.

This will then then be followed by Foley and then sound design. The reason Foley will be done (for all ribbons end) is because some of the Foley needs to be processed as sound design e.g. put through a sound effects to replicate the sound of a phone call.

The film will then be mixed. This may involve bouncing each different section (output of each role) into different STEMs e.g. dialogue, Foley, sound design, music. Another stem will be atmospheres, this may not be a stem that is commonly used but I feel that creating an atmosphere stem makes it easier to control the level of background noise compared with everything else.